‘Black Men and White Girls’: the Limehouse Riot Trial of 1919

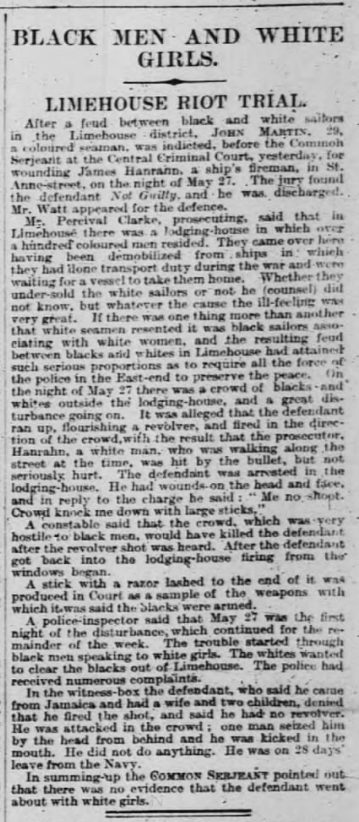

One hundred years ago today, on July 1st 1919, The Times reported on a trial at the Old Bailey resulting from a race riot in the East End of London a few weeks before. (The article is pictured and the full text has been transcribed here for ease of reading.) John Martin, a Jamaican serving in the Royal Navy, was charged with wounding a white sailor with a pistol during a disturbance outside a lodging house for black sailors in Limehouse, on May 27th. This incident was just one of the many episodes of racial tension and violence that were to be found in numerous port cities around the United Kingdom in the fraught and febrile year of 1919.

The Times, July 1st 1919

Background: post-war demobilisation and the competition for work

In the twelve months following the end of the First World War in November 1918, Britain demobilised almost three million men from its armed forces, men who naturally returned home and expected to find work. During the war years, however, an enormous number of workers from around the world – from the British Empire and elsewhere – had arrived to fill the places of those called up for military service, creating tensions over access to jobs for returning demobbed soldiers. A common assumption at the time seems to have been that the newcomers ought to be fired to make way – if they were black. Given that many of the non-British workers in the merchant marine were from West Africa and the Caribbean, small black communities formed particularly in port cities, sometimes alongside existing communities of Black British citizens, creating the conditions for problems in these places.

Starting with an outbreak of violence in Glasgow in January, race riots happened around the country until late in the summer, including in South Shields, Liverpool, Hull, Cardiff, Salford, Newport and elsewhere. There were several separate outbreaks in the East End of London, in Poplar and Canning Town as well as Limehouse.

Violence in Liverpool and the murder of Charles Wootton

Some of the worst of the violence happened in Liverpool. An especially notable incident in this city was the murder of Charles Wootton, a young Bermudan who had served in the Royal Navy during the war. On June 5th 1919, Wootton was pursued by a mob through the streets of Liverpool to the Queen’s Dock; despite the presence of the police, he was chased into the water by the crowd (by then perhaps two thousand strong) who pelted him with stones. Struck on the head, Wootton sank and drowned.

Charles Wootton in his Royal Navy uniform

In recounting this story in his excellent work Black & British: a Forgotten History, David Olusoga comes to a striking and disturbing conclusion: given the circumstances, including the public nature of the act and the inability or unwillingness of the law to determine who was at fault, we have to see Wootton’s death as a lynching. This is a very sobering word to encounter when reading about the Britain of only a hundred years ago, and should make us reassess our assumptions about British law and order.

Moreover, in David Olusoga’s book I was particularly struck by this sentence, about the wider disturbances in Liverpool during this period:

“The violence in Liverpool was orchestrated by well-organised gangs, hundreds and sometimes thousands strong, who hunted black men on the streets.”

David Olusoga, Black & British: a Forgotten History, 2016

I found this a truly shocking thing to learn about a British city in the twentieth century. For context, this was only 41 years before the Beatles formed in the same town; it is astonishing to think that this kind of mass racial attack could happen in the same year that Jon Pertwee (i.e. Dr Who) was born. My point being that it was a Britain on the cusp of being recognisably our own Britain, a modern country of pop music and sci-fi on the television.

Sexual jealousy in the race riots…

The competition for jobs was one of the two big reasons behind the racial tensions of 1919. Besides this, the disturbances were frequently attributed to unhappiness at relationships between black men and white women. Sexual jealousy among white men (meaning in fact, of course, fear of sexual inadequacy) was often cited in press coverage as the explanation for violent outbreaks.

…but racism at the root

I say ‘two reasons’, but of course they are actually only one: defining the black men as something else, as ‘the other’. Meaning that it all comes down to racism. An important point to note is that of the foreign workers who came to Britain to meet wartime labour needs, there were many Europeans, including Danes, Swedes, Poles and Russians. There were never, however, any anti-Scandinavian riots… Indeed, on occasion such visitors joined in with the attacks on black men, demonstrating that racial identity was the sole basis for choosing sides, not economic competition between returning Brits and foreign workers.

The Limehouse trial

In the case of the trial of John Martin following the Limehouse disturbance, it became very clear that sexual jealousy was a primary factor. As The Times reported it, this was what bothered the white mob most:

“Mr. Percival Clarke, prosecuting, said that in Limehouse there was a lodging-house in which over a hundred coloured men resided. They came over here having been demobilised from ships in which they had done transport duty during the war and were waiting for a vessel to take them home. Whether they under-sold the white sailors or not he (counsel) did not know, but whatever the cause the ill-feeling was very great. If there was one thing more than another that white seamen resented it was black sailors associating with white women…”

The Times, July 1st 1919

Besides the prominence of the female company question, this extract is remarkable for how the prosecuting barrister presents the economic issue – that black sailors might perhaps be guilty of having ‘under-sold’ white sailors. This is a breath-taking way of reframing the unpleasant fact that for many decades black seamen were routinely paid significantly less than white seamen, being seen as a cheap and easily exploited source of labour. Suggesting that this was somehow a competitive strategy voluntarily pursued by the black sailors themselves is exceptionally cheeky, even for a barrister.

Sir Henry Fielding Dickens, Common Serjeant, pictured in the 1890s

Was the justice system doing its job?

A crucial point to note is that, as the article from The Times clearly states in its first paragraph, John Martin was found not guilty and was discharged. One might therefore perhaps be keen to conclude that, despite all the unpleasantness, the system of justice was working, even if the verdict of not guilty did not eliminate the stress, severe inconvenience, and assault on dignity involved in an arrest and trial. However, the critical phrase to note is the remark from the judge in the case, the Common Serjeant (who was, incidentally, Sir Henry Fielding Dickens, a son of the novelist Charles Dickens). As The Times notes in closing their report:

“In summing-up the COMMON SERJEANT pointed out that there was no evidence that the defendant went about with white girls.”

The Times, July 1st 1919

Martin thus seems to have been cleared of the charges not because of the specific evidence respecting the firearm in question or the alleged shooting, but because it was established by the court that he did not mix with white women. This brings us to a powerful point made by Jacqueline Jenkinson: the deeply disturbing implication is that at the time, a black man could only really be regarded as innocent if he had no connection to white women. Any black man who did mix with white girls was seen as fair game for the mob.

Important to note here is that the Common Serjeant was the second most important judge in the Old Bailey; appointed by the Crown, he had a range of other high duties of state besides hearing criminal trials. This attitude, in which black innocence was dependent on avoidance of white women, thus came from the top and represented, by definition, the view of the establishment. For absolute clarity, inter-racial relationships were not illegal, and it is therefore bizarre and very troubling that this factor was even mentioned by the judge in his summing up.

It is also worth reflecting on the fact that even though the court established that John Martin had no history with white women and was found innocent of all charges, The Times still chose to headline their report as “Black Men and White Girls”, a slightly salacious title that surely reflected widespread interest – perhaps somewhat prurient – in this subject among the general population, even including the well-heeled types who would customarily read the national paper of record.

Finally, it is also important to note that, even though John Martin was released in this instance, in other cases from 1919 it is clear that black defendants were more likely than whites to be found guilty and to receive significantly harsher sentences.

Betrayed loyalties and the hypocrisy of the Empire

As was recognised even by the prosecutor in the Limehouse case – who was, after all, doing his best to put John Martin in prison – the black men under discussion had served Britain during the war. An essential point here is that there was no conscription in West Africa or the Caribbean, meaning that every single one of these men was a volunteer. As they saw it, they were loyally doing their bit for their Empire, and often had to overcome extraordinary obstacles to be allowed to serve.

In these circumstances, one might perhaps have expected rather more gratitude from Britain and British people. Instead, these men were rewarded with official indifference, social and judicial discrimination, and sometimes violence. The shoddiness with which the Empire treated some of the supposed subjects of the King further exposes the hypocritical immorality of the imperial project.

Further reading:

David Olusoga, Black and British: a Forgotten History, 2016

Jacqueline Jenkinson, Black 1919: Riots, Racism and Resistance in Imperial Britain, 2009