Hannah Arendt and Frantz Fanon: violence, empire and the nature of evil

A textual introduction by Paddy Docherty

Originally presented to Readings in Political Philosophy, Strathmore University, Nairobi

March 2021

Introduction

In this paper I will introduce two of the most stimulating and controversial thinkers of the twentieth century: the political theorist and refugee from Nazi Germany, Hannah Arendt, and the psychiatrist and anticolonial militant, Frantz Fanon. We will look at some of their key works, themes, and some areas of overlap between them, as well as considering their different outlooks and some associated problems.

Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt – life and works

Born in 1906 to a middle class, secular Jewish family in Germany, Hannah Arendt excelled at school, though also demonstrated something of a rebellious streak. In the 1920s she studied philosophy at the universities of Berlin, Marburg and Heidelberg, including under the leading philosophers Martin Heidegger, Karl Jaspers and Edmund Husserl; in 1929 she submitted her doctoral thesis on the nature of love in the work of St Augustine. Despite this strong background in philosophy, however, in later life she consistently refused the label “philosopher”, declaring herself to be a political theorist.

Following the rise to power of the Nazi regime in January 1933, Arendt began researching German antisemitism, leading to her arrest and interrogation by the Gestapo, as well as eight days in prison. On her release, she fled the country and travelled to Paris, where she remained for several years, working for Zionist organisations and assisting the emigration of many Jewish refugees to Palestine. In the spring of 1940, in anticipation of a German invasion, the French government ordered Arendt into the internment camp at Gurs; in the chaos following the fall of France to the German army, she managed to escape the camp in July and lived for a time as a fugitive. Eventually, she was able to obtain an American visa and papers allowing her to travel to Portugal, where she lived for a few months while awaiting passage across the Atlantic. Arendt arrived in New York (along with her husband) in May 1941. This was to be her home for the rest of her life.

In the United States, Arendt worked for several years as a writer and editor, then from the early 1950s onwards taught at several of the leading universities in the country, including Princeton, Yale, the New School and UC Berkeley. A heavy smoker, Arendt died of a heart attack at the age of 69 in 1975.

The first major book published by Arendt is also one of her most famous: The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951). Immediately establishing her as a leading thinker on the political ructions of the twentieth century and the associated ideologies, this heavyweight work seeks to trace the origins of the Nazi and Stalinist regimes in historical antisemitism and in European imperialism. Though it is not without significant problems (as we will see below), the relevance of this work to the politics of the early twenty-first century has added to something of a popular revival of interest in Arendt in the present era.

In 1958, Arendt published The Human Condition, in which she sets out her detailed analysis of the vita activa (the human “life of activity”, as opposed to the vita contemplativa, the “life of the mind”). This is a dense text and a challenging read, so is much less well-known to general readers; it is replete with the carefully defined systems of categorisation that became something of a trademark of Arendtian thinking. Though this work is largely outside the scope of this introduction, we will touch on one important element below, as it could be argued that The Human Condition contains the key to understanding Arendt’s political and philosophical outlook as a whole.

In the popular mind, Arendt is often most associated with her book Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), along with the surrounding controversy. Beginning as a series of articles for The New Yorker magazine, this work was based on Arendt’s attendance at the 1961 trial in Israel of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann. She uses this event to examine the Holocaust and the question of who bears responsibility, as well as to reflect on the nature of evil. We will consider Eichmann in Jerusalem below, along with the uproar that it caused.

Also in 1963 came Arendt’s next major work, On Revolution, in which she compared the French and American revolutions of the late eighteenth century, particularly in terms of her framework of categories developed in The Human Condition. For Arendt, the French revolution was a failure because its leaders became concerned with the wellbeing of the masses, while the American republic was a success because it remained focused on strictly political liberty.

Amid the student rebellions and popular protests of 1968, Arendt wrote On Violence, which began life as an article (1969) and was then published in book form (1970) before being included as part of the anthology The Crises of the Republic (1972). Again employing her strict categorisations of human activity, this work contains some highly problematic statements and some direct criticism of Frantz Fanon, as we will explore below.

When she died in 1975, Hannah Arendt left an unfinished text which was later published as The Life of the Mind (1978). Many of her articles, notebooks and correspondence were also published posthumously by friends and supporters, comprising a significant body of work and helping to maintain interest in her life and ideas.

Frantz Fanon

Frantz Fanon – life and works

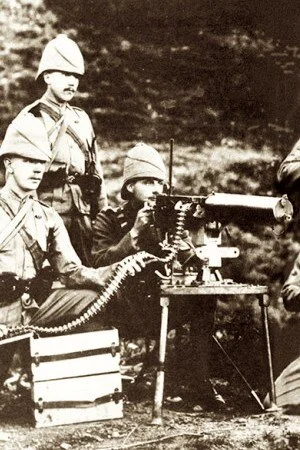

The Caribbean island of Martinique was still a French colony when Frantz Fanon was born there in 1925. Coming from a prosperous middle-class family, he was able to attend the most prestigious school on the island, though WWII interrupted his education. In 1943 he joined the Free French army and served in North Africa and France, being decorated with the Croix de guerre after being wounded in action in 1944. After the war, Fanon returned to Martinique to complete his high school education, then went to France in 1946 to study medicine. He qualified as a psychiatrist in 1951, and served two years in France in this capacity.

In 1953, Fanon made a decision that would determine the course of the rest of his life: he moved to the French colony of Algeria to take up an appointment at a psychiatric hospital at Blida-Joinville, just outside the capital of Algiers. Less than a year after his arrival, the Algerian war of liberation broke out in November 1954, and Fanon gradually became increasingly drawn into the Algerian resistance against the French colonial administration. He secretly joined the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) in 1955, while maintaining his work in the French hospital, where he treated the psychological ailments of both Algerian victims of torture and their French torturers. This period was crucially formative in his writing and world outlook.

By late 1956 his activities were becoming known to the authorities and Fanon resigned very publicly from his post at the hospital; he left the country in December 1956, moving to the neighbouring and newly-independent state of Tunisia to continue his work for the FLN. He wrote extensively for the FLN newspaper El Moudjahid, served as Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Government of Algeria, and worked on opening a ‘third front’ across the Sahara Desert. By 1960 he was becoming increasingly ill, and in early 1961 Fanon was diagnosed with leukemia. After seeking medical treatment in both the Soviet Union and the United States (ironically under the supervision of the CIA), Fanon died in December 1961 at just 36 years old.

Frantz Fanon’s first book was Black Skin, White Masks, published in France in 1952. In a curious mix of psychoanalysis and literary criticism, Fanon analyses the problems of identity created by colonialism for the colonised subject, and the psychological toll of colonial racism. To a great extent, this reflects his shock at experiencing racism as a Black man in France, despite his level of education and his status as a decorated war veteran.

In 1959, Fanon published an account of daily life in Algeria during the liberation war; though the original French title translates as Year Five of the Algerian Revolution, this book is best known in Anglophone countries as A Dying Colonialism. In several themed chapters (women in the liberation struggle, radio broadcasts, medicine, the family), Fanon charts the changes in Algerian society under the conditions of war.

Fanon’s most famous work, The Wretched of the Earth, was published just a few days before his death in 1961. As we will explore below, this landmark book frankly addresses the violent nature of colonialism and the role of violence in liberation, as well as detailing the psychological impacts of colonial oppression.

Finally, a selection of Fanon’s articles and other writings was published posthumously in 1964 as Toward the African Revolution. Mainly comprising articles from El Moudjahid on racism, the liberation war, the psychological and psychosomatic impact of colonialism, etc, this collection also includes his 1956 public letter of resignation from his hospital appointment.

Contrasting world views

Although Arendt and Fanon were contemporaries and wrote about some of the same phenomena, they approached the world in very different ways, using quite different mental models to understand systems and events.

In addition to being a committed anticolonial activist, Fanon was also a Marxist, so his natural way of perceiving the world was through the standard bourgeois/proletariat class struggle binary; applied to the world as a whole, the oppressed peoples of the European colonial empires formed a kind of global proletariat class in his thinking. Although there are therefore some directly Marxist elements in his writing, the anticolonial side is by far the dominant, and much more defining of Fanon as a thinker.

Arendt, on the other hand, determinedly rejected any ideological systems and insisted on maintaining her independence from any particular school of thought. Though she had been an active Zionist in the 1930s and early 1940s, she broke with mainstream Zionism in the 1940s when the leading organisations moved away from inclusive models for a future Israel and began planning for a strictly Jewish state. Though she was very familiar with the works of Karl Marx (and wrote of him with respect), she rejected Marxism along with all the other bold Modernist visions for reshaping the world, including nationalism, fascism and so on. Indeed, given her categorical dismissal of Modernist projects, and her explicit avowal of ancient political forms, I would suggest that we might regard Arendt as in fact an anti-modernist. Additionally, a recurring concern for Arendt was uncertainty – she writes often of the problem of the unpredictability of life, a characteristic that one might perhaps think resulted from her sometimes traumatic life experiences.

If we return briefly to The Human Condition we can see the importance to Arendt of political models from classical antiquity. Although The Human Condition is itself outside the scope of this introduction, it contains Arendt’s model of the vita activa which, I would argue, is the essential key to understanding so much of the Arendtian view of the world. While it may appear to be at first glance somewhat abstract, I will therefore briefly summarise this concept as a valuable tool for engaging with Arendt.

Taking the polis of Periclean Athens as her basis, Arendt viewed all human activity as falling into a hierarchy of three categories:

Labour was concerned with subsistence, with meeting the basic necessities of life. Fundamentally biological, this was activity directed to keeping the physical body alive and capable of reproducing: obtaining food and water, etc. By their nature, the products of labour are consumed and are therefore not lasting.

Work for Arendt means the creation of things, the making of an artificial world by reshaping the environment and its resources to human requirements. This raises human life above mere nature. Buildings, infrastructure, books, works of art, etc, all come under this category. The products of work have a degree of durability.

Action corresponds to the Aristotelian concept of praxis: the speaking and acting together of free citizens. The realm of action is the public space in which citizens appear before each other as equals, and are presented with the opportunity to distinguish themselves by undertaking new beginnings or launching heroic projects. The goal and end product of action is therefore glory, or lasting renown, a form of immortality.

It is abundantly clear from her writings that for Arendt, this is a hierarchy not merely of status but also of value: action is prized above all other forms of activity, and she makes a categorical distinction between action, which forms the public realm of politics, and both work and labour, which remain in the private realm. For Arendt, it was only by entering the public realm that a person can become truly human, and on occasion throughout her works, she refers with some disdain to persons who remain in the private realm.

We can see that this Arendtian schema of the vita activa becomes problematic when we realise that it is based upon a strict social hierarchy. The realm of action is open only to free citizens, which in classical Greece might amount only to perhaps 10-20% of the population. Everyone else (women, slaves, foreigners) were restricted to the private realms of work and labour, it being their role to provide the means that would enable the citizen to enter the realm of action by being freed from furnishing his own necessities of life.

While this model of human life might be regarded as anachronistic (and certainly Arendt is frequently criticised for her adoption of antique categories), we can see how it can apply to societies much more recent than the Greek city states of 400BC. For example, in the new American republic of the late eighteenth century, which Arendt was very keen to defend, we can view the political class of wealthy, white, male, slave-owners as the free citizens, who could busy themselves with founding a republic; everyone else (women, enslaved Africans, Native Americans, the poor) remained locked into the private realm by law and by their biological need to obtain food and other necessities of life.

More broadly, the vita activa hierarchy could also be interpreted as applying to modern capitalism, such that most people are constrained by the need to earn a living and only a privileged few have the resources to properly function in the public realm of action.

Arendt’s vita activa model therefore informs much of her thinking and her value judgements about groups of people, so it is worth bearing in mind when approaching her work. We will return to it shortly to examine the real meaning of some of her theorising.

Violence

A significant area of overlap between Fanon and Arendt is in their focus on violence, and its nature and consequences. Fanon is especially associated with the embrace of violence, largely because of The Wretched of the Earth and above all its first chapter, “Concerning Violence”, which is often labelled “notorious”. In her short book on the subject, Arendt seems to reject violence on principle, once again using her system of categories to condemn its destructiveness. On the face of it, therefore, it may seem that Fanon advocates violence and Arendt denounces it. Is this really the case?

The Wretched of the Earth was and remains a book of outstanding importance because it is perhaps the most articulate expression of the violent nature of European colonialism ever committed to the page. Often the focus of commentators is on Fanon’s ready acceptance of the use of violence in order to counter colonial oppression, but the principal achievement of the work, especially in “Concerning Violence”, is to set out powerfully how structural violence is the defining characteristic of empire:

For centuries the capitalists have behaved in the under-developed world like nothing more than war criminals. Deportations, massacres, forced labour and slavery have been the main methods used by capitalism to increase its wealth, its gold or diamond reserves, and to establish its power.

The Wretched of the Earth, Ch 1, “Concerning Violence”, p. 80

Fanon’s depiction of colonialism contrasted with the mainstream European presentation of their empires as being concerned with the ‘civilising mission’ or promotion of free trade, undercutting their claims of a positive impact around the world. When the structural violence of empire is understood in the way depicted by Fanon, violent opposition might seem more acceptable to an objective observer, especially when the undemocratic character of European colonies is also considered:

…colonialism is not a thinking machine, nor a body endowed with reasoning faculties. It is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence.

The Wretched of the Earth, Ch 1, “Concerning Violence”, p. 48

Moreover, the all-encompassing nature of colonial regimes, and the long period during which they had often ruled in Africa or Asia, had led to wholesale destruction of local societies. An accomplished author of polemic as well as an astute analyst, Fanon writes stirringly about this ruinous impact of European occupiers:

The violence which has ruled over the ordering of the colonial world, which has ceaselessly drummed the rhythm for the destruction of native social forms and broken up without reserve the systems of reference of the economy, the customs of dress and external life, that same violence will be claimed and taken over by the native at the moment when, deciding to embody history in his own person, he surges into the forbidden quarters.

The Wretched of the Earth, Ch 1, “Concerning Violence”, p. 31

Fanon is often criticised for ‘glorifying’ violence; such a charge requires us to look at the texts for evidence of his motives for accepting violent means of liberation. Arguably, he embraced violence not for its own sake but precisely because it had utility – given the strength of the colonial regimes, perhaps it was the only available strategy likely to lead to successful liberation. In Fanon’s reading, since colonialism was itself based on violence, it would not yield to polite requests. This reflects its totalnature, comprising not just rifles and gunboats but rather a total system of domination, including in the mental sphere:

The fight carried on by a people for its liberation leads it, according to circumstances, either to refuse or else to explode the so-called truths which have been established in its consciousness by the colonial civil administration, by the military occupation, and by economic exploitation. Armed conflict alone can really drive out these falsehoods created in man which force into inferiority the most lively minds among us and which, literally, mutilates us.

The Wretched of the Earth, Ch 5, “Colonial War and Mental Disorders”, p. 237

Indeed, for Fanon a key area of the utility of violence was in restoring the humanity and agency of the colonised, by repairing their psychological distress:

At the level of individuals, violence is a cleansing force. It frees the native from his inferiority complex and from his despair and inaction; it makes him fearless and restores his self-respect.

The Wretched of the Earth, Ch 1, “Concerning Violence”, p. 74

For some critics, this amounted to the ‘glorification’ of violence that they condemned, but such statements might best be seen in the context of the wholesale impact of colonisation that Fanon described. Indeed, it might be argued that a tactical error made by Fanon was in his use of sometimes emotionally-charged and dramatic language, rather than any error in his understanding or logic. Some phrases open him up to easy attack by opponents; take for example, this striking image:

For the native, life can only spring up again out of the rotting corpse of the settler.

The Wretched of the Earth, Ch 1, “Concerning Violence”, p. 73

Finally, for Fanon an important aspect of the utility of violence was in helping to ensure a genuine decolonisation, rather than a withdrawal in name only, which might leave economic and strategic ties with the former colonial master that could amount to continued dependence:

True liberation is not that pseudo-independence in which ministers having a limited responsibility hobnob with an economy dominated by the colonial pact.

Liberation is the total destruction of the colonial system, from the pre-eminence of the language of the oppressor and “departmentalisation”, to the customs union that in reality maintains the former colonised in the meshes of the culture, of the fashion, and of the images of the colonialist.

Toward the African Revolution, Ch 7, “Decolonisation and Independence”, p. 105

Hannah Arendt was one of the critics of Fanon: in On Violence she several times attacks his alleged glorification of violence, and also witheringly objects to the inspiration that the student movements of 1968 found in The Wretched of the Earth. The main thrust of her short book, however, is to counter the prevailing notion among political theorists of all stripes that violenceis just the most flagrant manifestation of power.

The importance of her models from classical antiquity can be seen in the development of her argument. For Arendt, power is narrowly defined as the human ability to act in concert, reflecting her definition of action in The Human Condition. Consensus and reaching agreement through debate is the essential characteristic of power in her definition, ideal qualities that would be abolished by the intrusion of violent coercion. Although she admits that power and violence are usually to be found together, the distinction is an important part of Arendt’s categorisation:

To sum up: politically speaking, it is insufficient to say that power and violence are not the same. Power and violence are opposites; where the one rules absolutely, the other is absent… Violence can destroy power; it is utterly incapable of creating it.

On Violence, Part II, p. 56

Arendt grants that sometimes violence may be required in limited circumstances (self-defence in a physical assault, for example), but even then she declares that “Violence can be justifiable, but it never will be legitimate”. [On Violence, Part II, p. 52] Her valorisation of power (meaning consensus, action, praxis) above always-illegitimate violence appears to make On Violence a firm rejection of violence and its role in any form of politics.

However, this raises what seems to be a contradiction of central importance. As we know from The Human Condition, Arendt viewed politics as taking place strictly in the public realm of action, being characterised by the speaking and acting together of free citizens. We can therefore see how her definition of power applies to this level of the vita activa hierarchy, and that violence would have no place within this: consensus would be impossible. Outside of the realm of action, however, Arendt’s apparent rejection of violence suddenly disappears. In The Human Condition, she is explicit about the role of violence beyond the political realm:

What all Greek philosophers, no matter how opposed to polis life, took for granted is that freedom is exclusively located in the political realm, that necessity is primarily a prepolitical phenomenon, characteristic of the private household organisation, and that force and violence are justified in this sphere because they are the only means to master necessity – for instance, by ruling over slaves – and to become free. Because all human beings are subject to necessity, they are entitled to violence towards others; violence is the prepolitical act of liberating oneself from the necessity of life for the freedom of the world.

The Human Condition, Chapter II, p. 31

Therefore, in the Arendtian model of human life, power operates exclusively in the realm of politics, while the employment of violence is an acceptable means for free citizens to elevate themselves into the sphere of action:

Though she does not use the term, Arendt is thus describing very significant structural violence being employed to maintain the political status of the elite minority comprised of free citizens. This puts a very different gloss on her apparent rejection of all violence as illegitimate in the pages of On Violence. Given this apparent contradiction in Arendt’s thinking, and Fanon’s utilitarian approach to the use of violence, we must surely therefore re-examine the general acceptance of Fanon as pro-violence and Arendt as anti-violence.

Colonialism

It will be clear from the passages considered above that for Fanon, colonialism and violence were inextricably linked: colonialism was the systematic exploitation of the rest of the world by the European empires, using violence and racism among other tools of domination. In his analysis, both these phenomena were necessary elements of the colonialist strategy:

Torture in Algeria is not an accident, or an error, or a fault. Colonialism cannot be understood without the possibility of torturing, of violating, or of massacring. Torture is an expression and a means of the occupant-occupied relationship.

Toward the African Revolution, “Algeria Face to Face with the French Torturers”, p. 66

Similarly, the maintenance of racial division was an essential part of the overall effort to sustain colonial domination:

Racism, as we have seen, is only one element of a vaster whole: that of the systematized oppression of a people.

Toward the African Revolution, Part II, “Racism and Culture”, p. 33

For Fanon, then, colonialism was a murderous disgrace, with no redeeming features. Seldom had an author written so trenchantly about the reality of the European empires:

This European opulence is literally scandalous, for it has been founded on slavery, it has been nourished with the blood of slaves and it comes directly from the soil and from the subsoil of that under-developed world.

The Wretched of the Earth, Ch 1, “Concerning Violence”, p. 76

Arendt, on the other hand, had a rather different view. In The Origins of Totalitarianism she devoted an entire section of the book to a discussion of imperialism, though in her own very specific definition. Rather than use what might be regarded as a standard distinction between imperialism and colonialism (in which “imperialism” describes the exercise of power over, while “colonialism” expresses taking possession), Arendt defined imperialism in quite a unique way, which we will come to shortly. Firstly, let us consider her views on settler colonialism.

Once again working within her hierarchy of categories, Arendt regards the founding of a colony as a quintessentially political act, belonging in the realm of action. For Arendt, placing the phenomenon of settler colonialism into this category thereby gave it intrinsic value. In striking contrast to Fanon, Arendt even described it as one of the “outstanding forms of achievement” [Origins, p. 243] of the European peoples.

In order to sustain her positive view of settler colonialism as a manifestation of action, Arendt had to maintain the myth of terra nullius, meaning “land belonging to nobody”. She appears to embrace the European colonialist idea that societies in other parts of the world were insufficiently developed to be worthy of any consideration. For example, she is very dismissive of the peoples of entire continents:

Colonization took place in America and Australia, the two continents that, without a culture and history of their own, had fallen into the hands of Europeans.

The Origins of Totalitarianism, Part II, “Imperialism”, p. 243

It is notable that Arendt recognises that violence was involved in settling what she calls these “sparsely populated territories”: she mentions that “colonization of America and Australia was accompanied by comparatively short periods of cruel liquidation” [Origins, p. 243, note 4], but, importantly, this is relegated to a footnote and is passed over with no further discussion; she seems to take the view that colonisation of some parts of the world was nonetheless justified:

The world of native savages was a perfect setting for men who had escaped the reality of civilization. Under a merciless sun, surrounded by an entirely hostile nature, they were confronted with human beings who, living without the future of a purpose and the past of an accomplishment, were as incomprehensible as the inmates of a madhouse.

The Origins of Totalitarianism, Part II, “Imperialism”, p. 248

Moreover, it seems clear that Arendt is making a value judgment about the original inhabitants of these areas. Writing of European colonisers entering the “silent wilderness” of Africa, she suggests that they found a land…

…where an untouched, overwhelmingly hostile nature that nobody had ever taken the trouble to change into a human landscape seemed to wait in sublime patience…

The Origins of Totalitarianism, Part II, “Imperialism”, p. 249

Reinforcing this apparently diminished view of at least some non-European peoples, Arendt is explicit that, in terms of her vita activa hierarchy, they existed only in the realm of labour. In her terms, that meant that they were not fully human:

They were, as it were, ‘natural’ human beings who lacked the specifically human character, the specifically human reality, so that when European men massacred them they somehow were not aware that they had committed murder.

Moreover, the senseless massacre of native tribes on the Dark Continent was quite in keeping with the traditions of these tribes themselves.

The Origins of Totalitarianism, Part II, “Imperialism”, p. 251

Even if Arendt reaches these conclusions primarily through the use of her systems of categorisation, I would suggest that this has to be recognised as one of the recurring incidences of racial prejudice that mar her work. There is an ongoing debate on the question of Arendt’s racism, with some of her defenders seeking to excuse her various offensive remarks as “injudicious” or as “misjudgements”, while critics have been robust and comprehensive in their cataloguing of the evidence of her racism. In her book Hannah Arendt and the Negro Question, published under the name Kathryn T. Gines, the American scholar Kathryn Sophia Belle has fully analysed Arendt’s racist attitude on the issue of school segregation in the southern United States of the 1950s, and makes an unarguable case that Arendt harboured racist views. This is not the place to enter upon a full discussion of the instances of racism in Arendt’s work but there is clear and highly problematic evidence of anti-Black racism in several of her works. In my view, this requires us to reconsider her tendency to elide colonial oppression and her lack of interest in structural violence.

This tendency of Arendt may also be reflected in her definition of imperialism, which is decidedly Eurocentric. For her, “imperialism” began with the Scramble for Africa of the 1880s and included the Pan-Slav and Pan-German movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: the dynamic that concerns her is therefore European vs European competition, rather than the exercise of European power in other parts of the world. To the extent that the latter is included in this area of her consideration, it is essentially limited to the potential for “blowback”, in which methods or doctrines of coercion might be perfected in the colonies and later imported for use on European populations. Characterised by expansion for its own sake and aggression against other European polities, imperialism in the Arendtian definition was not concerned with founding new political entities in what might be claimed as terra nullia, and was therefore not justified in terms of her definition of action. For this reason, she rejects imperialism on principle, but it is essential to note the Eurocentric focus of this condemnation.

Totalitarianism

In this Eurocentric way, Arendt developed the argument that the boomerang effect of colonialism was an essential part of the emergence of totalitarian movements in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century. Quite distinct from mere dictatorship or tyranny, totalitarianism aimed at domination over people of a total and merciless kind:

Totalitarianism in power uses the state administration for its long-range goal of world conquest and for the direction of the branches of the movement; it establishes the secret police as the executors and guardians of its domestic experiment in constantly transforming reality into fiction; and it finally erects concentration camps as special laboratories to carry through its experiment in total domination.

The Origins of Totalitarianism, Part III, “Totalitarianism”, p. 513

Rather than simply aiming at the seizure of power (which might, for example, be the goal of a standard fascist dictatorship), totalitarianism was characterised by plans fully to remake human society, based on notions that had become detached from reality and required an environment of untruth; an all-encompassing system of oppression was necessary to maintain such a regime:

…thanks to its peculiar ideology and the role assigned to it in this apparatus of coercion, totalitarianism has discovered a means of dominating and terrorizing human beings from within.

The Origins of Totalitarianism, Part III, “Totalitarianism”, p. 426

Significantly, Arendt defined both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union under Stalin as totalitarian regimes – the key similarity lay in their methods of domination, not their ideological claims, which in any case were entirely mythical and opportunistic:

Practically speaking, it will make little difference whether totalitarian movements adopt the pattern of Nazism or Bolshevism, organize the masses in the name of race or class, pretend to follow the laws of life and nature or of dialectics and economics.

The Origins of Totalitarianism, Part III, “Totalitarianism”, p. 409-10

An aim in common was to render people superfluous, and to convince them of their own superfluity: this is why the concentration camp and arbitrary arrest were valued tools of totalitarian systems. By destroying the expectation that law and administration would follow some fairly rational order, individual morale and any possibility for collective consciousness would be attacked. Unpredictability and deliberate ambiguity were employed to the same end. Moreover, totalitarianism was not a form of nationalism, for it was willing to render superfluous its own people too:

The Nazis did not think that the Germans were a master race, to whom the world belonged, but that they should be led by a master race, as should all other nations, and that this race was only on the point of being born. Not the Germans were the dawn of the master race, but the SS.

The Origins of Totalitarianism, Part III, “Totalitarianism”, p. 538-9

Being German was not therefore enough for the Nazi regime to value an individual: Germans too were targets. Hitler planned to exterminate in due course many categories of “useless eater”, even people with heart problems or lung disease:

That the Nazi engine of destruction would not have stopped even before the German people is evident from a Reich health bill drafted by Hitler himself.

The Origins of Totalitarianism, Part III, “Totalitarianism”, note 16, p. 406

Additionally, a defining characteristic of totalitarianism was the impossibility of it accepting others. All-consuming, reliant on continual expansion and the creation of new enemies, totalitarian regimes offered no prospect of a peaceful equilibrium:

…total domination is the only form of government with which coexistence is not possible…

The Origins of Totalitarianism, “Preface to Part III: Totalitarianism”, p. xxxiv

Despite the colonial boomerang effect being an essential part of her theorising in this area, Arendt does not make a connection between the features of totalitarianism that she described in Europe and the practices of colonialism. Fanon, on the other hand, makes an explicit link:

The colonial world is a Manichaean world. It is not enough for the settler to delimit physically, that is to say with the help of the army and the police force, the place of the native. As if to show the totalitarian character of colonial exploitation the settler paints the native as a sort of quintessence of evil.

The Wretched of the Earth, Ch 1, “Concerning Violence”, p. 31-32

Although he does not labour the point, Fanon makes it clear that he regards the forms of rule of Nazi Germany and the European colonial empires to be broadly comparable:

Not long ago Nazism transformed the whole of Europe into a veritable colony.

The Wretched of the Earth, Ch 1, “Concerning Violence”, p. 80

One of the imperial developments that Arendt discussed as a platform for totalitarianism was the development of colonial bureaucracies. She argued that officials returning from the colonies brought home new and more brutal forms of administration that were also increasingly depersonalised by the development of more complex systems of government. Having explored this theme in Origins, Arendt returned to it in On Violence, by which time she saw the lack of accountability made possible by the anonymity of bureaucracy as an alarming threat to political freedoms:

…the latest and perhaps most formidable form of such dominion: bureaucracy or the rule of an intricate system of bureaus in which men, neither one nor the best, neither the few nor the many, can be held responsible, and which could properly be called rule by Nobody.

On Violence, Part II, p. 38

Totalitarian bureaucracy and the role of the individual within it were the themes of Arendt’s most controversial work: her report into the trial of Adolf Eichmann.

Eichmann and the nature of evil

Adolf Eichmann was a middle-ranking SS officer who played a crucial role in the Holocaust by heading the transport department of the Gestapo and thus supervising the mass transportation of Jews from around Europe to the extermination camps. He managed to flee Germany after the war, but in 1960 was kidnapped in Argentina by Israeli secret agents and brought to Jerusalem for trial on a series of war crimes charges. Hannah Arendt proposed to The New Yorker that she travel to Israel to cover the proceedings, and this resulted in a series of articles in 1963, shortly followed by her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.

Arendt used the trial testimony and, especially, the transcripts of Eichmann’s lengthy interrogation after his arrest, to give not just an account of the role of the defendant but of the mechanics of the Holocaust as a whole. Evidently seeking to be factual rather than tactful, and willing to be blunt in her language, she succeeded in causing a storm of protest on the publication of the articles.

One of the controversies resulted from her characterisation of Eichmann and her associated musings about the nature of evil. Watching him in the courtroom, Arendt was struck by his mediocrity and by his limited capacity to speak without resorting to stock phrases and clichés:

The longer one listened to him, the more obvious it became that his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think…

Eichmann in Jerusalem, Ch III, “An Expert on the Jewish Question”, p. 49

Expanding on Eichmann’s character, she described him by using language that some readers evidently felt to be making light of a dark subject, or somehow excusing the defendant from some portion of his responsibility:

…it was essential that one take him seriously, and this was very hard to do, unless one sought the easiest way out of the dilemma between the unspeakable horror of the deeds and the undeniable ludicrousness of the man who perpetrated them, and declared him a clever, calculating liar – which he obviously was not.

Eichmann in Jerusalem, Ch III, “An Expert on the Jewish Question”, p. 54

Despite all the efforts of the prosecution, everybody could see that this man was not a “monster”, but it was difficult indeed not to suspect that he was a clown.

Eichmann in Jerusalem, Ch III, “An Expert on the Jewish Question”, p. 54

Arendt’s observations of Eichmann as a mere nobody – a mid-rank bureaucrat unable properly to think as he dutifully went about the murder of millions of people – led her to frame her conclusion in terms of “the banality of evil”. This famous phrase occurs only once in the text (at the end of Ch XV) but was given prominence in the book’s subtitle, and has created much misunderstanding. While many readers and commentators at the time regarded it as somehow trivialising the atrocious deeds under discussion, others have read it to mean that all evil is in some way necessarily banal. It is an unfortunate phrase that does not effectively communicate what Arendt intended to say.

The point she is making is that evil does not always appear in the form of demonic villains, but also in ordinary, unremarkable people who can be capable of monstrous deeds if they have abandoned their moral responsibility. In a sense, it is therefore also a plea for applied philosophy: lack of thinking can lead us to ruination. We should not mythologise evil and imagine that it accompanies only grandly gothic malefactors, but be ready to recognise it in everyday places and people. Importantly, this concept does not offer Eichmann any kind of reprieve: Arendt supported the imposition of the death penalty for his crimes against humanity.

Another controversy sparked by Arendt’s work on Eichmann is her discussion of Jewish cooperation in the logistics of the Holocaust. Although she is factually accurate in relating these details, her phrasing and note of accusation is deeply untactful in the circumstances and was highly offensive to many Jewish people:

Without Jewish help in administrative and police work – the final rounding up of Jews in Berlin was, as I have mentioned, done entirely by Jewish police – there would have been either complete chaos or an impossibly severe drain on German manpower.

Eichmann in Jerusalem, Ch VII, “The Wannsee Conference, or Pontius Pilate”, p. 117

Although Arendt does make the point that there was nothing that the Jews and Jewish leaders could have done in the face of such overwhelming force, it was obscured by the more numerous passages that appeared to blame the victims themselves. Of particular notoriety is this bleak statement:

To a Jew this role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest chapter of the whole dark story.

Eichmann in Jerusalem, Ch VII, “The Wannsee Conference, or Pontius Pilate”, p. 117

The uproar surrounding Eichmann in Jerusalem is so closely connected with her public image and reputation that the recent biographical film Hannah Arendt (dir. Margarethe von Trotta, 2012) is centred entirely around this period of her life and work.

Conclusion

In this brief overview of the work of Arendt and Fanon we have considered their major works and looked at some of the key themes, problems, and controversies involved. Casting a fleeting eye over the entire corpus of an author’s writing in this way can valuably highlight both the development in their thinking and any hidden contradictions or disconnections. We can see how conclusions or categorisations from one area of a thinker’s work can have serious implications when applied in others, most especially in the example of Arendt’s strict categorisations of her vita activa hierarchy and what it means for her views on underdeveloped countries and their people.

A pressing question concerns, of course, the issue of whether they remain relevant in the early twenty-first century. Arendt wrote in the context of the Cold War and her alarm at the potential destruction of the human race in a nuclear Armageddon, but she has seen a particular resurgence of interest in the last few years: Amazon briefly sold out of The Origins of Totalitarianism on the day after Donald Trump was elected president… Given her own racial prejudice and her rigid categorisations of people, however, is she in fact an appropriate inspiration for the Black Lives Matter generation?

Is Fanon’s work relevant only for the colonial era long ended, or do his analyses also apply to the world we live in now? Has decolonisation everywhere been as complete as he would have wanted? In closing, a quick example of Fanon’s remaining appeal. In his bracing new book How to Blow Up a Pipeline (Verso Books, 2021), the Swedish academic and climate activist Andreas Malm sets out an agenda for increasingly militant action to combat climate destruction, including using violent means to target fossil fuel infrastructure. He ends his book by quoting Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth, invoking the anticolonial spirit to call for action to a rather different end.

Works cited

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 1951, Penguin Books (2017)

--, The Human Condition, 1958, University of Chicago Press

--, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, 1963, Penguin Books (1977)

--, On Revolution, 1963, Faber & Faber

--, On Violence, 1970, Harcourt

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 1952, Grove Press (2008)

--, A Dying Colonialism, 1959, Grove Press (1967)

--, The Wretched of the Earth, 1961, Penguin Books (1967)

--, Toward the African Revolution, 1964, Grove Press (1967)

Kathryn T. Gines, Hannah Arendt and the Negro Question, 2014, Indiana University Press